Honolulu’s Chinatown has changed significantly from its incarnation in 1954, the year I set my third novel, Char Siu, in its streets and establishments. Today, in a real sense, it’s neither “China” (Vietnamese and other ethnic Southeast Asian businesses have moved in) nor “town” (most business owners in the district no longer also reside there). There are, however, a handful of businesses that still preserve the Honolulu Chinatown of Char Siu and as a result, are my personal favorites.

I make a trek into Chinatown as often as I can, which turns out to be once a month or so. It’s really my favorite place on the island, being one of the last genuine places in a city rapidly falling prey to the whims of developers attempting to line their pockets with absentee landlord dollars. Sure, it’s got a screaming addict or muttering eccentric on every block and it smells like a beach park men’s room where nobody manages to hit the urinal, but that’s all part of the charm. It makes the red brick buildings redder, and the food and drink inside the establishments taste like special occasion fare.

My Chinatown visits will often include a banhmi lunch at a favorite Vietnamese restaurant with friend and mentor Don Wallace of The Hawai‘i Review of Books (THROB) and Honolulu Magazine, or dropping in on another friend and mentor, the warrior-poet Wing Tek Lum (whom I affectionately refer to as the Dean of Chinatown) at his family business which also doubles as physical inventory space for my publisher, Bamboo Ridge Press (Wing Tek is, in addition to being an award-winning poet, Bamboo Ridge’s Business Manager).

If there is time, I try to visit Skull-Face Books & Vinyl, an eclectic shop containing both new and used titles, including a well-curated crime fiction section where I’ve found Ross MacDonald paperbacks and a collection in translation of works by Japanese Taisho Era (My friend Pat Patterson would say, appropriately, “Greater Taisho”) mystery writer Edogawa Rampo (Come on, where else are you going to find this cool shit in a brick-and-mortar?).

An obligatory stop on the Chinatown tour is always at Sing Cheong Yuan bakery.

Here in Hawai‘i, we don’t have “seasons” the way the rest of the nation does. We only have one real season, something that can be described as a temperate summer. It’s one of the things that makes living here wonderful. Yeah, I hear the whining all the time from mainland expats about how they miss the “change of colors”, but they never complain about not having to shovel snow from the walkway in January or not being eaten alive by chiggers and gnats in July. While I’d love the chance to wear my tweed more often, I’ll take our gentle, endless summer any day over the trauma to my sinuses I endured in college in New York City. One of the greatest by-products of a lack of seasons is being able to get “seasonal” foods and goods all year round.

Mooncakes, one of my favorite “seasonal” delicacies, are usually only available around the time of the Moon Festival (not to be confused with the Lunar Festival or Lunar New Year) which happens sometime in the fall (usually mid -September to mid-October). Sing Cheong Yuan makes them available all the time. They’re palm-sized baked goods with a perfect crust surrounding various fillings. Though I like them all, my favorites are the Black Sugar and White Lotus versions. I usually cut them into six bite-sized pieces at my desk with my Laguiole pocket knife and enjoy them with Uji matcha (best green tea on the planet) or Kona coffee (best coffee on the planet and another fringe benefit of living here).

I went through quite a few Sing Cheong Yuan mooncakes—sometimes with coffee or tea, sometimes with 12-year-old Highland Park—while squeezing out the first draft of Char Siu. The taste, along with the water-like notes of Bill Evans’ “Love Theme from ‘Spartacus’” (anachronistic by a decade, I know, but it worked) helped me to visualize a Maunakea Street of a different decade, where cops whose parents and grandparents made it to Hawai‘i plantations under the wire of the federal exclusion acts clashed with criminals who came after those acts were repealed.

Sing Cheong Yuan also makes the best sesame peanut candy, a staple confection enjoyed by Hawai‘i residents of all ethnic backgrounds for generations, including my Japanese parents and grandparents who introduced me to its delectable taste and its contradictory gooey-and-crunchy texture. As historic testament to the Chinese sweet’s popularity among Honolulu’s Japanese population, the Japanese merchant-dominated shopping building, Aala Rengo, believed by many to be Honolulu’s first shopping center, was home to a single Chinese business known particularly for its sesame peanut candy. Aala Rengo, located in the heart of a Japantown which no longer exists, was just a stone’s throw away from Honolulu’s Chinatown, but it was as if Japantown needed its own source of sesame peanut candy.

Sing Cheong Yuan’s manapua (that’s the Hawai‘i term for char siu bao) is my favorite, both its baked and steamed iterations. Here in the islands, our bao are not the cute little buns that come three to a small bamboo steamer in dim sum houses across the mainland. Ours are hamburger-sized, meant to be a meal for sugar plantation workers of a different era. Sing Cheong Yuan’s are big.

I can probably blame the curse of social media for the long lines to get into the small customer space in the bakery. There are times, though, in the mid-afternoon when the lines are not as bad. Wing Tek Lum had recently penned a stanza in which he captures perfectly the elation at finding the entrance to Sing Cheong Yuan without a human queue (Here it is with the Dean of Chinatown’s generous permission):

I was passing by Sing Cheong Yuan and noticed there wasn’t any line outside. So I quickly went in and found prepackaged trays by the counter, round plastic ones with transparent covers, filled with new year’s treats— colorful dried fruit that were steeped in syrup, which they charged by the weight. I couldn’t believe my luck, I didn’t have to wait. I chose one with my favorite candied melon, sliced lotus root, carrots, and ginger, the fibrous pineapple and coconut strips— all meant as a sweet bribe to the kitchen god, though no one today believes in such village superstitions. We just like the sweets.

Though the shop was founded in 2008 (according to a piece in Honolulu Magazine, the family ownership took over a 40-year-old bakery and renamed it), the flavors are true to the ones I was introduced to as a young child, which is the era following the era of my books.

Whenever I want something the detectives and criminals from my pages might have enjoyed, nothing beats the bakery on Maunakea Street, even with the line of Instagram parasites.

It’s worth the wait.

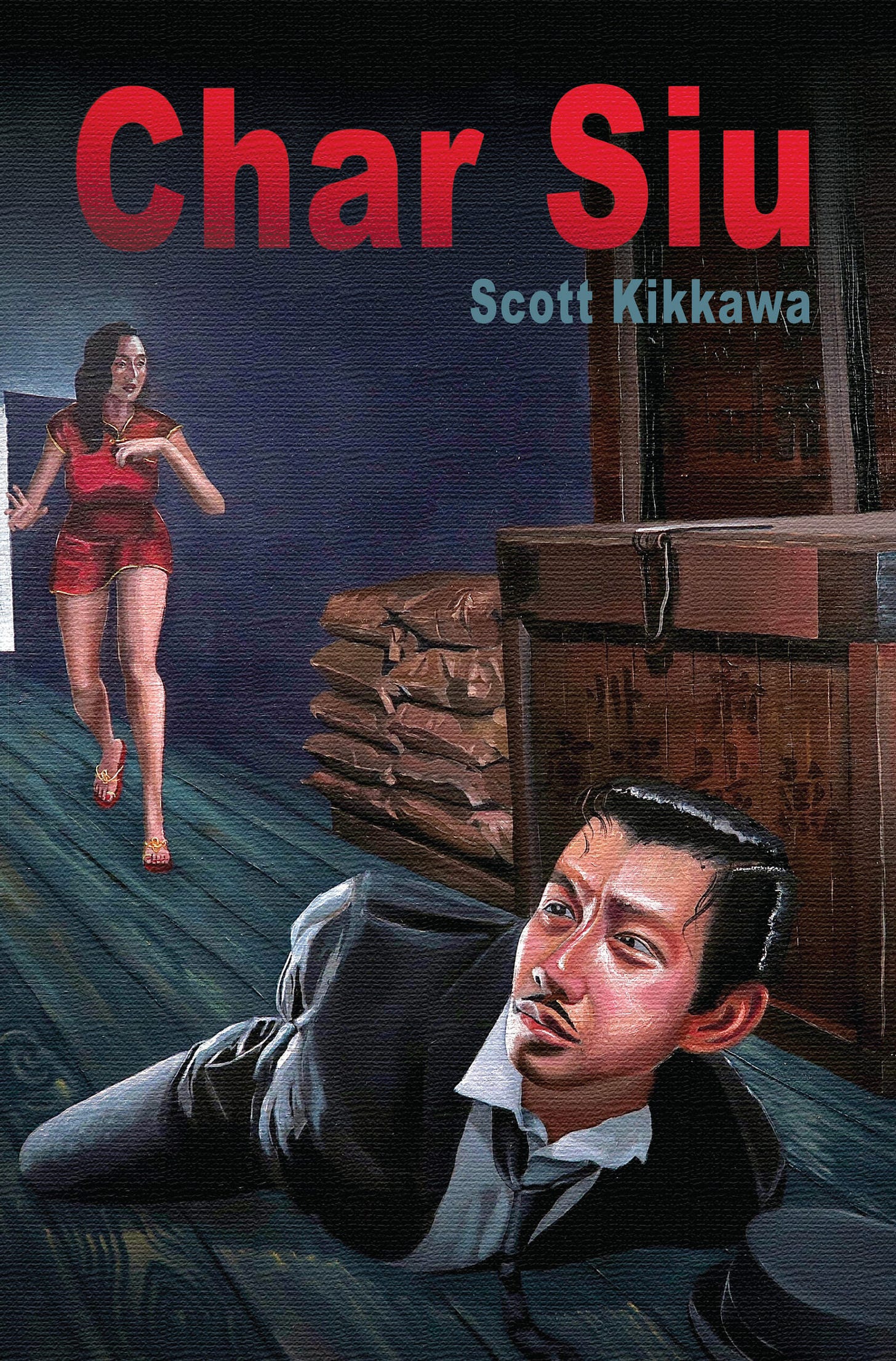

Read Char Siu for a lead-laced taste of my Honolulu Chinatown.

I love how "Mooncakes All Year Round" invites readers on a journey through Honolulu Chinatown. The reader tags alongside the trek through Chinatown, “sees” everything, through the descriptive language, the drug addiction problem hidden in the shadows of the buildings to the charms of food and drink establishments. The historical context of Chinatown, how it developed over the years, and even some of the people who make Chinatown so special such as Bamboo Ridge Press’s Wing Tek Lum color our journey. Then and only then, after we have been given the context and history surrounding Sing Cheong Yuan Bakery, do we arrive. By adding such details, Sing Cheong Yuan Bakery’s significance is highlighted not only as a place where they sell delicious char siu manapua, but what shaped its beauty, its taste: the culture, the history, and the people.

Nostalgic memories of lotus and egg yolk mooncakes colored my palate today. Thank you, Mr. Kikkawa!